The Szwarc/Schwarz Family Saga – Part 1

If while walking in the paved narrow streets of “Le Marais”, the historical Jewish Quarter located in the heart of Paris, you decide to stop for a moment on the corner of rue Aubriot and rue Sainte Croix de la Bretonnerie and lift your head up, your eyes will fall on a small statue of a Lady, hiding in a niche. Below the statue, a Latin inscription on the building wall Ecce mater tua as well as the name of the street (Sainte Croix de la Bretonnerie) may very well lead you to conclude the statue is that of the Virgin Mary. Yet, you will be unable to find out more about it, as no indication (yet) is there to help you.

Why a Virgin Mary in a Jewish Tour of Paris ?

You may be puzzled for a second, before you enter the heart of the Jewish quarter, “The Pletzl”, assuming most reasonably and plausibly that the statuette has nothing to do with your Jewish tour…

Yet, as we already know – and nowadays more than ever – things are not as obvious as they may seem…

So here’s the story behind this small sized Virgin Mary in terra cotta.

Who is Marek Szwarc ?

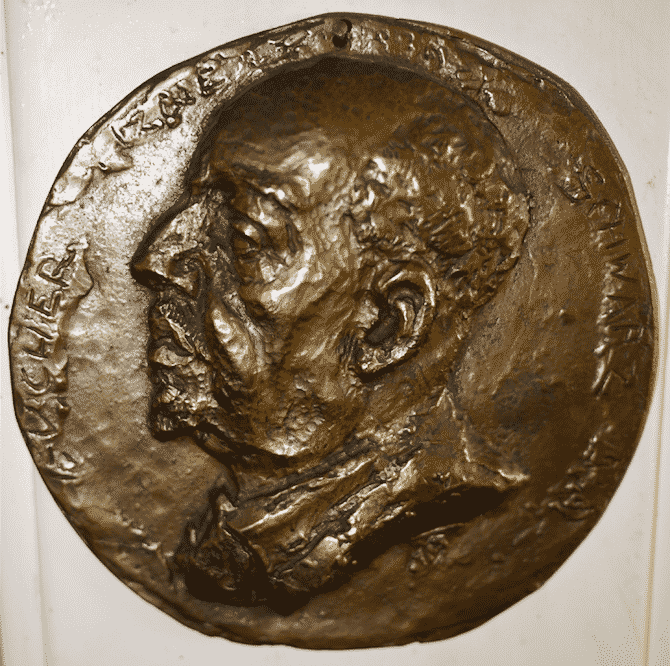

The sculptor is Marek Szwarc (the polish spelling of Schwarz), born in 1892 in Zgierz, a small town near Lodz (Poland). He was the youngest of ten brothers and sisters. His father, Isucher Moshe Szwarc (1859-1939), although an orthodox Jew, joined very early the intellectual movement of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment) and became an ardent Zionist activist. The house of the Szwarc’s family also became to be the heart of the local Jewish intelligentsia and Isucher’s vast library, a reference regarding Judaica.

In 1910, at the age of 18, the young Marek, who had already shown a passion for arts, decided to go to Paris and was accepted to the École des Beaux Arts. During his first Parisian years, he boarded at La Ruche (“the beehive”) the renowned artists’ residence in Montparnasse, where he met Fernand Léger, Amedeo Modigliani, Chaim Soutine, and Marc Chagall…

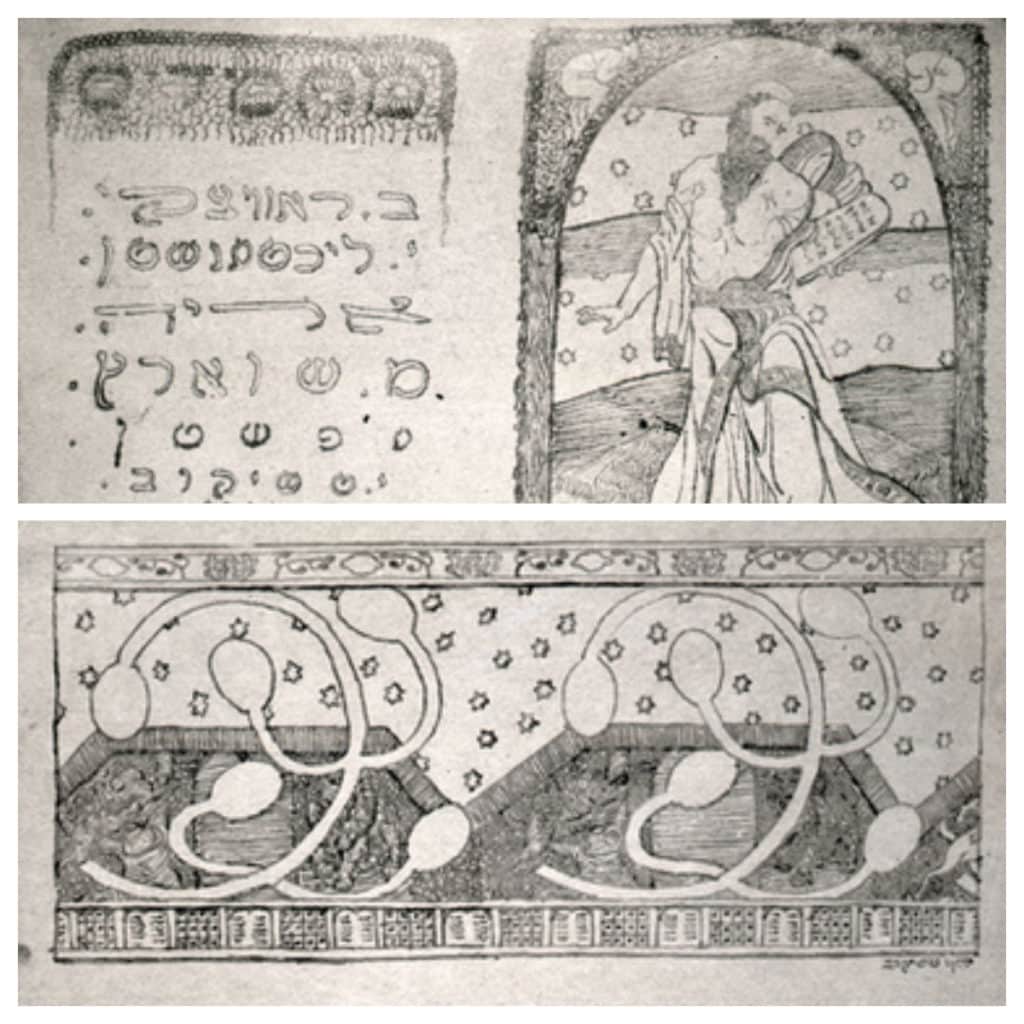

In 1912, together with other artists, Marek launched the first Jewish art journal Makhmadim (a Hebrew word for “Lovely things”) in which some of his first paintings appeared.

The Circle of Yung Yiddish

During the First World War, Marek returned to Poland.

In his journeys to Odessa, he met with some of the leading Jewish intellectuals and writers such as Haïm Nahman Bialik, Ahad Ha’am and Mendele Moïkher Sforim. In 1918, back in Lodz, he met the poet Moyshe Broderzon and together with other artists and writers, they founded the Jewish literary and avant-garde circle the Yung-Yidish.

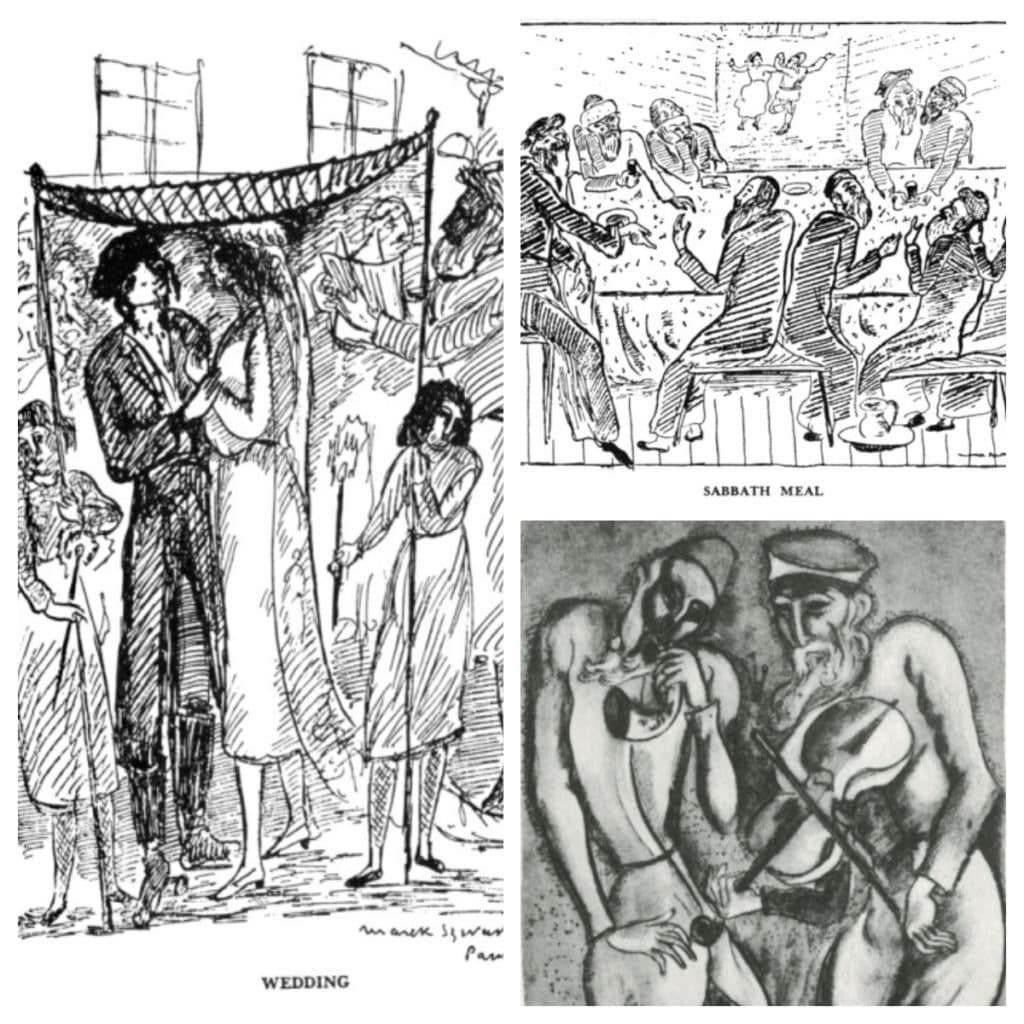

The group explored new styles, held exhibitions and founded a newspaper of the same name.

Their main inspirations were both Chagall’s paintings, with his fascination with the primitive folk art of Jewish Chassidic folklore, and with German expressionism.

The Search for Spirituality

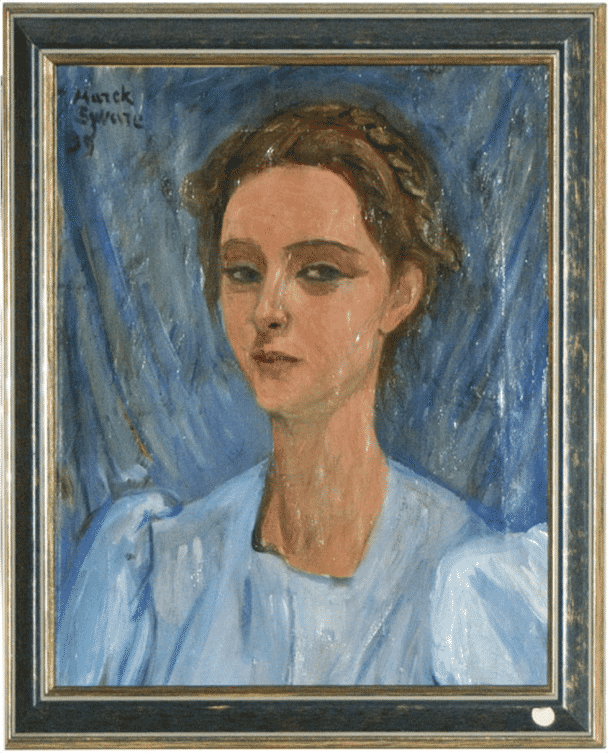

Marek’s works at that time – paintings and graphics – dealt principally with social and existential issues, as well as with Catholic iconography. His sculptures already pointed out his growing quest for “spirituality”.

They may have very well been inspired by Chagall’s crucifixions, in which Jesus is represented as a Jewish martyr (allusions to the horror of the Pogroms).

After the war, Marek met and married Eugenia (Guina) Markowa-Pinkhus, a Polish Jewish writer. In the early 1920s, the couple settled in Paris, where they remained until World War II.

Marek’s work from this period was frequently involved with biblical themes from the Old and New Testament. Indeed, the most decisive moment in his life, was his conversion along with that of his wife, to Christianity, in 1920. As Irmina Gadowska shows in her remarkable article on Marek’s search for spirituality, the conversion of Marek represents a rather exceptional case: while for many assimilated Jews, converting was an alternative to orthodox Judaism and often an “entry ticket” to the environmental society, or to a career, Marek’s conversion embodied for him a step in his religiosity and self-improvement. His religious reorientation resulted from his fascination with Christ as a symbol of universality. Indeed, inspite of his conversion, Marek did not abandon his Jewish identity, which, in his opinion, connected him more strongly with Jesus and, moreover, enabled him to realize his desire “to be a Jew of the Catholic Faith”. During this time, Marek remained an active member of the Yung-Yiddish. A number of his linocuts appeared in yet another Yiddish journal: the radical literary expressionist Albatross, edited by the poet and journalist (and future politician in Israel) Uri Zvi Greenberg. In 1925, Marek published an article entitled: “The National Element in Jewish Art”.

Tereska Torres

In 1922 Guina gave birth to the couple’s daughter, Tereska – who, came to be known as Tereska Torres and whom we will meet in another chapter. As her parents did not reveal publicly their conversion, Tereska kept this secret until the age of ten. In the 1920’s Marek gained worldwide recognition. His works were exhibited in France, as well as in various countries in Europe, Canada and the United States. In 1932, he is invited by Meyer Levin – who later marry Tereska, and became a renowned American journalist and novelist – to illustrate the book The Golden Mountain, an anthology of legends on Hassidic Jews in Eastern Europe.

Revelations of Marek

During the 1930s, Marek’s conversion was no longer a secret.

As one can imagine, its revelation was a terrible shock to his close Jewish friends and to his family in Zgierz (particularly affected was his mother, who remained closer to orthodox Judaism). Marek was henceforth cut off from the Jewish artistic community in Poland. Deeply moving, and highly interesting, was the reaction of his elder and beloved brother Samuel whose restless research and investigations led to the discovery of the existence of hundreds of secret or Crypto Jews (known as “Marranos”) living in the North-East regions in Portugal, i.e. who continued to practice in secret some form of Judaism, more than 400 years after the forced conversion of Jews in Portugal (we will find Samuel in the next chapter of the Schwarz’s family). Samuel had great admiration for his young brother (it was he who lodged Marek in Paris during his first years at the Beaux Art). He managed to overcome his deep sorrow of Marek’s conversion, which he later understood in the context of Marek’s tenuous pursuit of mysticism.

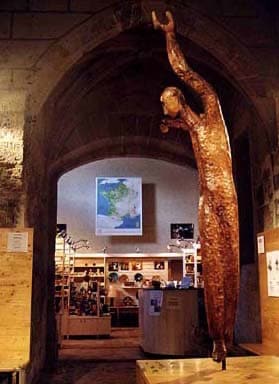

The 1930’s were the years in which Marek produced some of his most astonishing works in hammered copper and was recognized as one of the leading religious artists in France.

International Exposition of Art

In the 1937 International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life, he was commissioned to create bas-relief in iron for the pontifical pavilion. Another commission which he received a year before, brings us to our starting point: the statuette we noticed on the street corner in the Jewish quarter of Paris. At the instigation of an art Association created within the framework of an artistic movement promoting the production of works of art accessible to all, Marek was put to this task. The occasion was the Tercentenary of the vow of Louis XIII of 15 August 1638 which placed France under the protection of the Virgin Mary. Marek thus created this statuette, using his daughter Tereska as a model for the sculpture. As you can see in the image below, “Notre Dame de toutes les Grâces” (Our Lady of all graces), was installed in the Marais in 1938.

At the outbreak of World War II, Marek joined the Polish army in exile in Scotland, while his wife and daughter fled via Lisbon to England. After the war, the family returned to Paris. Marek moved to his studio at 65 boulevard Arago (Cité Fleurie), where he remained until his death on December 28th 1958.

During his last years, Marek devoted his time mainly to sculpting in stone and wood and casting in bronze. His last masterpiece was “Libera me”, a sculpture in olive wood, which can now be seen at the Jouarre Abbey.

Marek’s works are on display today in various museums, and private collections in France, Poland, England, Israel, Canada, Venezuela, and the United States. In recent years, three Jewish Museums acquired various important collections of his works: the Jewish Museum of Art and History in Paris, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw (POLIN), and in Jewish Museum in Lisbon (currently under construction).

Some of Marek’s work

In 2014, his home town, Zgierz, honored Marek by dedicating a street in his name.

Finally, on one of your next visits in the Marais, when reaching the corner of rue Aubriot and rue Sainte Croix de la Bretonnerie, you will see beneath the statuette of the Virgin Mary, a plaque with Marek’s name that the City Hall of Paris plans to inaugurate in 2021.

Part 1 : a Curious Virgin Mary in the jewish quarter of Paris

Continue Reading Part 2 : Marek’s daughter Tereska : A Jewish family of all Arts !

Continue Reading Part 3 : A journey around the world !

Meet the Author of the Article : Livia

Livia is a Tour guide in Paris

http://www.desgensinteressants.org/marek-szwarc/index.html

For further reading:

Irmina Gadowska, “In Search of Spirituality. Religious Reorientation or Radical Assimilation? The Case of Marek Szwarc” in Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts, vol. XVII, 2015, p. 347-369.