Schwarz’s Family Part 2 : Marek’s Daughter Tereska

Introduction

While walking in the Jewish quarter, in the heart of the Marais, you may come across this curious statue of the Virgin Mary.

Installed in the Marais in 1938, the statue is the work of the painter and sculptor Marek Szwarc (link), whom we met in another chapter of this journey… The model for this “Lady of all Graces” was Marek’s daughter, Tereska.

You can read my First Chapter here

Born into a Jewish family in Poland, Marek Szwarc, arrived to Paris in 1910 where he became one of the prominent artists of the Avant-guarde movement. After the First World War, Marek married the novelist and poet Guina Pinkus and the couple settled in Paris. Their daughter, Tereska, was born on 3 September 1920.

Her Jewish Parents converted Catholicism

A few months before her birth, Marek and Guina, converted to Catholicism.

Tereska was baptized and later placed in a convent school. The conversion of her parents was kept secret in order to avoid the resentment of their Jewish families. Tereska at her parent’s request, was compiled to remain silent. When Tereska was 13, the conversion of her parent’s was reported in the world Jewish press, and naturally caused the estrangement from the family. Tereska later recalled this period of her childhood and the heavy burden of this secrecy in her book, The Converts (1970).

Tereska’s Jewish identity never left !

In 1937, at the age of 17, Tereska began her literary career with her first novel Sand and Foam, which was published in 1946 under the pen name of George Achard. When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, Tereskas’s father, although converted to Catholicism, felt that “as a Jew I must fight against Hitler”, and enlisted in the Polish force, created within the French army. After fighting in the Polish Armed Forces in France Marek joined the Free Polish Forces in Scotland.

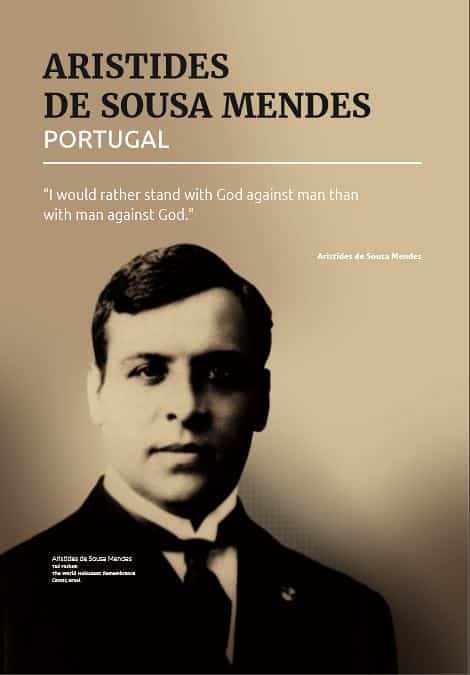

In June 1940, Tereska and her mother, who remained in France, quickly understood the dangers they faced under the Nazi Occupation, and sought to reach Great Britain, in hops of joining Marek. Passing through Saint-Jean-de-Luz near the Spanish border, then Bayonne, they were able to enter Portugal, thanks to the heroic action of the Portuguese Consul in Bordeaux, Aristides de Sousa Mendes, who, against the orders of his government, granted hundreds of entry visas to all those who needed them. Sousa Mendes was recognized in 1966 by Yad Vashem as one of the “Righteous among the Nations”.

Tereska and her fight against Nazis

Prior to leaving for London, Tereska and her mother arrived in Lisbon where they met Tereska’s uncle – Marek’s elder brother – Samuel Schwarz, the “discoverer” of the Marranos in Portugal, whom we will meet again in yet another chapter of this saga.

Immediately upon her arrival in London in November 1940, Tereska, at the age of 19, was among the first women to join the Free French Forces founded by the government-in-exile of Charles de Gaulle.

Quick Note : Charles de Gaulle was very famous French Politic figure

During WWII, he was a French army officer and statesman who led the French Resistance against Nazi Germany, and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Republic from 1944 to 1946 in order to reestablish democracy in France

Tereska, initially serving as a rank-and-file soldier in London, she was later transferred to the press and information unit and then to de Gaulle’s main intelligence and operations unit.

Tereska’s Love Life

In 1943, Tereska fell in love with a young man, Georges Torrès, who was serving with the Free French Forces in London. Georges was the son of a famous Jewish lawyer, politician and writer Henri Torrès. His mother, Jeanne, who divorced Torrès, was then the companion of Léon Blum, Former French Prime Minister. (When Blum was imprisoned in Buchenwald, Jeanne asked the Vichy government to join him there, where they were eventually allowed to be married.)

After a brief courtship, Tereska and Georges Torrès were married in 1944. Three weeks later, Georges returned to France with the Free French Forces. Shortly after the liberation of Paris, he was killed in action on the Alsace front. Dominique, their daughter, was born four months after his death.

a Jewish Family of All ARTS !

Upon returning to France, Tereska, devastated by the loss of her husband, had to deal with the financial difficulties of the Post-War period. Tereska’s mother-in-law Jeanne and her husband Léon Blum, who survived Buchenwald and returned to France, sheltered and supported Tereska. It was at the Blum’s that she met Meyer Levin, American novelist and journalist, 15 years her senior, who in fact she had known in her childhood, as Levin had met her father Marek in the mid 1920s. (In another chapter we will of course find Meyer Levin, whose life story is as dramatic – and unbelievable – as his films and novels.) Retrospectively, in any case, we realize that this second meeting was one of this key-moments that shift lives…

In 1946, Levin asked Tereska to assist him as a script-girl in Palestine, where he was working on his film “My Father’s house”. Tereska thus found herself with her daughter, Dominique, in Jerusalem, where she members of Levin’s family.

The following year, Meyer Levin invited Tereska Torrès to embark on another cinematographic adventure which today is considered one of the first docudramas ever shot in cinema: The Illegals.

The film follows various Jewish refugees, survivors of the Holocaust, in Europe during 1947, in their perilous and arduous attempts to reach Palestine. It includes some rare footage of the “illegal immigration” (Alya Bet), prior to the creation of the State of Israel, to which Levin melded a fictional story of a young couple – the feminine figure, Sara, played by Tereska! In 1948, after the film was released, Tereska Torrès and Meyer Levin were married.

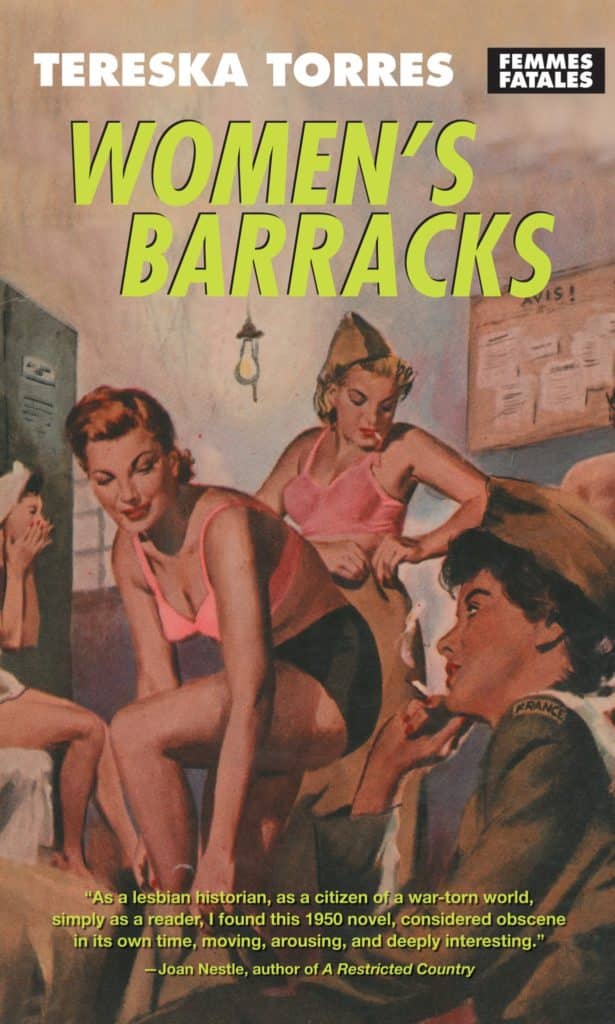

The same year, fascinated by Tereska’s stories of her experience within the Free French Forces, Levin encourages Tereska to adapt her wartime diary into a novel. Two years later, Tereska’s fictional account entitled Women’s Barracks (translated by Meyer Levin) was published in the United States, by Gold Medal Books

Its publication, in 1950, immediately caused a scandal, since while describing the women’s life in the barracks, it depicted lesbian relations among some of the unit’s members. Women’s Barracks quickly became “the first paperback original bestseller” selling over 4 million copies and translated in more than a dozen languages. This, despite the fact that in 1952 it was cited as an example of how paperback books were promoting moral degeneracy by the U.S. House Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials!

In Canada, the book was banned by a Court in Ottawa.

When the book was reprinted in 2005 by the Feminist Press in its “Femmes Fatales” series, it was acclaimed as having inspired a whole new genre of lesbian and feminist writing in the US during the 50s.

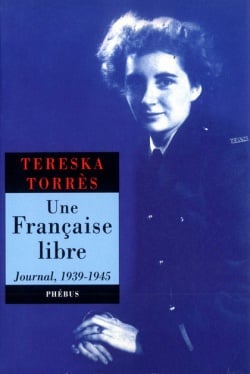

Tereska Torrès however, was quite bewildered to find that for years she had been considered a “pioneer of lesbian literature”. In several interviews she expressed dismay at what she saw as the public’s disproportionate fascination with the novel’s scenes of erotic love between women at the expense of all else: “There are five main characters in the novel, only one and a half of them can be considered lesbian. I don’t see why it’s considered a lesbian classic.” The fact remains that from Tereska’s 16 books, Women’s Barracks was the only one which received international success. In France, in adherence to Tereska’s wish, the book was not published until 2002 (in a revised edition). Two years earlier she published her wartime diary Une Française Libre.

In 1963, Tereska Torrès accompanied Levin to Ethiopia, where he filmed “The Fellashas”, the first documentary about the life of the Ethiopian Jews known as Beta Israel (“The House of Israel”) who would be “officially” accepted by Israel as orthodox Jews in the late 1970s, a recognition that was followed by a mass emigration from the 1980 to 2000. Tereska and Meyer returned to Ethiopia in 1970 to also document the life of some of the Fellashas, descendants of Ethiopians Jews, who converted to Christianism.

Tereska’s third and last visit in Ethiopia took place in 1984, three years after Meyer Levin’s death. Contacted by a humanitarian association, she agreed to go to Ethiopia to organize the clandestine departure of a group of Fellashas children to Israel, a mission that she recounted in her last book Mission Secrete (“Secret Mission”), published in 2010, four month before her death, in Paris, where she lived almost all her life.

In 2019, the City of Paris honored Tereska Torres by naming a new garden in her memory, situated on rue Laure Diebold in the 8th arrondissement: Jardin Tereska-Torrès-Levin.

Quelle femme, quelle vie!

What a woman , what a life !

Author

Livia

If you want to meet Livia and join our Jewish Walking Tour of le Marais , here is the link to contact me and I will book Livia for you !

http://www.desgensinteressants.org/tereska-torres/index.html